Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Here in the United States, we rarely hear much about what’s going on in the rest of the world. Our news media is so focuses on the latest scandal, many of which are of their own creation, that they tend to ignore what’s going on in other countries.

Yet every day, people around the world face crisis and disaster that we don’t hear about.

Such is the situation in Cape Town, South Africa today. There’s a countdown to disaster going on there, as the 3.7 million residents in the area race towards what is being called “day zero.” This is the day when the city runs out of water and it’s currently projected to be May the 11th; just a few short months away.

On that day, the city water authorities will be shutting off water to all but critical installations. People will be forced to get their water from centralized locations, carting it home. A maximum of 25 liters of water (6.75 gallons) per person, per day will be authorized until the day zero crisis is over.

While some people are trying to stockpile bottled water now in preparation, not everyone can do that.

So, what has brought the city to this point? Many say that it has been poor management of the municipal water supply. Accusations of leaky pipes that have not been repaired, poor management of the infrastructure and lack of planning abound.

video first seen on Guardian

But regardless of whether these accusations are true or not, the reservoir that Cape Town depends on for water is down to 26.3% of capacity, after three years of drought.

Government officials are blaming the current water shortages on global warming, which makes a handy scapegoat. But droughts have existed throughout the history of the world, regardless of whether global warming exists or not.

Not developing the necessary infrastructure to survive those droughts is irresponsible on the part of any government, essentially ignoring their responsibility to protect the people they are sworn to serve.

Currently, a massive water conservation campaign is going on in the city, as the residents pull together to extend the date for day zero. So far, this has added four days to the calendar. While that may not seem like much, it is a major victory, one that can be expanded upon.

One news interview of a resident shows how hard people are working to make this campaign work. The man stated that their normal water use was 19,000 liters (5,135 gallons) per month, but that the last month his family only used 8,000 liters (2,162 gallons); a reduction of 58%.

But that probably isn’t going to be enough. Further cuts will have to be made, unless the drought breaks and the reservoir fills once again.

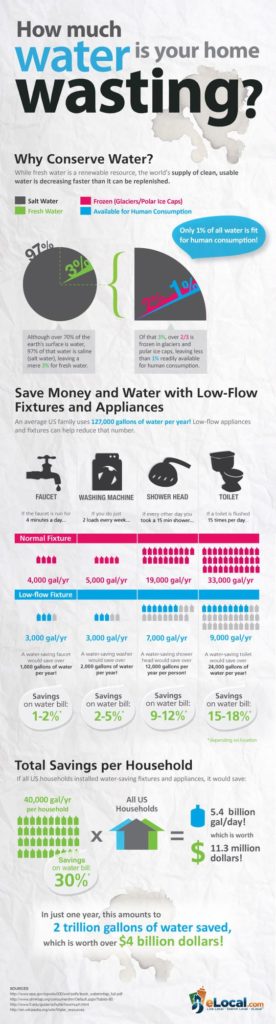

To put that in perspective, the average American uses 80-100 gallons of water per day. So, a family of four would use roughly 12,000 gallons of water per month, more than double what the middle-class South African family uses.

Of course, that interview was of a typical middle-class homeowner. The poor of South Africa, like the poor elsewhere in the world, get by with much less water than that.

Any time people don’t have running water available, and instead have to haul water from the local source, whether a natural source of a government installed community water pipe, they find ways of living on much less water.

I’ve spent time in the villages of Mexico, places where they didn’t have running water. Instead, each family had a water tank out front and the city water truck would come and fill it twice a week. That gave them 100 to 150 gallons of water to last three to four days; roughly 15 gallons per person, per day.

But that’s not the worst. If there is anywhere where people struggle with having enough water it is in sub-Sahara Africa. The norm there is for people to live on five gallons of water per person, per day. That takes care of drinking, cooking and cleaning, including bathing, washing clothes and washing dishes.

The big question this brings to mind is whether this sort of thing could happen here in the United States. Let’s be honest with ourselves a moment; we’re spoiled. We expect to turn the faucet on and have a virtually unlimited supply of clean, purified water to use.

But that doesn’t mean that it will always be that way. In recent years, we have seen a number of droughts plague various parts of our country. It seems like hardly a year goes by, where there isn’t one part of the country or another which is in drought.

A few years ago, I was in the Colorado Rockies and saw first-hand how low the reservoirs were at that time. Several states depend on the water from those reservoirs, which are filled by the melting winter snow.

Southern California, where a large part of the country’s produce is grown, has seen severe droughts over the last few years, and it is unlikely to get better soon.

Since the area is normally arid, the state has spent billions of dollars over the last few decades, in creating the necessary infrastructure to collect and transport water from the wet northern part of the state for use in farming the southern part.

But politics got in the way of practical reality, and the water which was intended for those farmers was instead flushed down-river to protect the delta smelt, a feed fish.

It is easy to say that this was a situation caused by mismanagement of the available resources. Had the politicians stayed out of the way, the drought would have been manageable and the farmers would have had enough water. But by allowing shaky environmentalism to overcome practical necessity, California’s government has put many of the state’s farmers out of work.

But that’s not the worst situation we face, as far as our water supply is concerned. The scariest piece of data to come forth is that the water level of several of our major aquifers is dropping. We are using the water from those aquifers at a faster rate than it can be replenished.

The aquifers most seriously affected by this are: the Canbrian-Ordavician Aquifer, the High Plains Aquifer and the two aquifers in Southern California.

These are the aquifer that provide water for a large part of the nation’s farming. So, water shortages in those areas means more than just a lack of water, it can lead to shortages in food as well. While water is a higher survival priority than food is, we need both of them to survive.

The reality is that you and I are subject to facing the consequences of those who control our water supply, as well as any natural disaster or drought. The economic, technological and military might of the United States can’t do a thing to stop drought. All we can do is prepare for it as best we can.

I don’t care where you live, unless maybe in the Pacific Northwest, rain is not consistent. There are wet spells and dry spells, and just about every resident who has lived anyplace can tell you when they usually are in that area. This is why our country has invested so much in building reservoirs, with over 84,000 dams in the United States.

The reservoirs allow us to have water during the dry spells; but even then, there is a limit to their capacity.

Of course, even if the reservoirs are filled to capacity, that water has to make it from the reservoir to our tap before we can use it. This makes the entire system dependent on electricity, the easiest part of our infrastructure to interrupt.

Blackouts which last more than 12 hours, can be accompanied by a lack of water pressure or even the water shutting off, just because there isn’t power to run the pumps.

The only solution for you and I is to have our own water stockpile. But more than that, we need a means of harvesting water from nature, so that we aren’t totally dependent on the system. That way, if something happens, at least we will have water, even if nobody else does.

This is really the only way we can protect ourselves from ending up standing in line, waiting our turn to get a few gallons of water, like the people of Cape Town. While we will probably still find ourselves having to ration water, at least we’ll have water to ration; and it will be our water, not water that the government can turn off or give away to some bait fish that we’ve never heard of.

There are actually three things we need to do here:

I’m not going to get into a detailed discussion about these three areas here, as there are other articles here on Survivopedia which do. But there are a few key things that I want to mention.

Water is difficult to stockpile, simply because of the vast amount of water we need. Since dehydrated water is only a joke, there is no real way of reducing the water’s volume, making it possible to store it in a smaller space. So the question then becomes, where can you find all that space?

I suppose if we all had the money to build an underground cistern or a private water tower, this wouldn’t be an issue. But we don’t; so we need a less-expensive alternative. That’s actually easier to find than you’d expect. All you need is an above-ground swimming pool, which you can buy surprisingly inexpensively.

The chemicals used to keep the water clean for swimming, are the same chemicals that make it safe for drinking.

The two basic means of harvesting water are rainwater capture and putting in a well. In both cases, there are legal ramifications that you have to consider, depending on where you live. Some states don’t allow rainwater capture and others limit who can drill a well. So before making a decision on this, you have to see what your state allows.

I’ve never liked the government telling me I can’t do something, especially if that something doesn’t hurt anyone else. So, just as a thought for your consideration, if I lived in a state where they didn’t allow rainwater capture, I’d put it in anyway.

To keep anyone from knowing what I was doing, I’d bury the water barrels, making it look like I had nothing more than a French drain for my downspouts.

New technologies are emerging, which show considerable promise. These focus on extracting moisture from the air. If you live in an area with high enough humidity to have fog, you can build simple fog catchers, which will allow you to convert the moisture in fog into drinkable water.

Other, more complicated technologies allow for extracting moisture from the air, even when there isn’t fog. These are still expensive, as they are new, but prices should drop as they become more readily available.

Any water you harvest needs to be purified, even rainwater. Birds tend to do things on the roof of our homes, which ensure that the rainwater we capture isn’t as clean as we might expect it to be. So don’t expect that water to be pure, if you haven’t purified it.

Likewise, well water can contain a considerable amount of bacteria, even when it comes from one of the deep aquifers. The only way of being sure that it is safe to drink is to purify it.

But water used for gardening, bathing, cleaning and flushing toilets doesn’t have to be purified. We use purified tap water for that now, just because it is cheaper to do that, than it is to put two water lines into every home, one for purified and one for non-purified water.

Be sure to have more than enough filter cartridges for your water filter, if you are using filtration to purify your water. Even the best cartridges only last so long, so put in a good stock.

No matter what you do to harvest water from nature, it’s probably not going to be enough, unless you also work to conserve water. The 100 gallons of water, per person, per day, that Americans use, is the highest rate of water consumption in the world.

People in South Africa are given a breakdown of water usage, that comes down to 50 liters per day. That’s a mere 13.5 gallons!

Many survival instructors say that you need one gallon of water per person, per day, for survival. But that’s just taking into consideration the water you need for drinking and cooking. It also doesn’t take into account hot temperatures. If you live in the Southwest, limiting yourself to that quantity of water could cause you to suffer severe dehydration.

Is it possible to live on the 13.5 gallons of water that they are recommending in South Africa? Yes, it is. But it means making some serous adjustments to our lifestyle. Take bathing for example; the average American bathes daily, using from 17 to 36 gallons of water per day.

But people in poorer countries can’t use that much water. Even in Latin American countries where they bathe daily, the average water consumption is much lower, with bathing accounting for only a gallon or two of water per day.

One of our biggest water wasters is flushing the toilet. Older toilets use as much as seven gallons of water per flush, while newer ones can be as low as 1.6 gallons per flush. So, changing out toilets can drastically reduce the water consumption of your family.

The other thing that can reduce it is not flushing every time it is used. Urine is biologically sterile, so unless the urine concentration in the water reaches a point of causing it to smell, there is no reason to flush every time you urinate.

But we have a water user that’s even bigger than toilets; that’s our lawns. With the large lots that we typically have for our homes (based on a world-wide average) and the fact that we all seem to plant lawns, we use an enormous amount of water keeping that grass alive.

To provide your lawn with one inch of imitation rainfall requires 62 gallons of water for every 10’ x 10’ area. So you could easily go through several hundred gallons of water in one day, just by watering your lawn.

I’ve lived in a couple of different arid areas during my life and I remember water rationing. During the rationing, we were only allowed to water our lawns certain days or not at all. When you’re living in a hot climate anyway, not being able to water your lawn could be enough to ensure its death.

Potential water shortages, even severe shortages, are no different than anything else that you and I prepare for. Like other potential disasters, the key is to be as self-sufficient as possible. That’s the only real protection for ourselves and our families.

Taking the actions I’ve mentioned above, as well as others you can find in this website, will ensure that you won’t be standing in line for hours, waiting to be able to get your daily ration of a few gallons of water. You and your family will be able to live a much more normal life, even if everyone else is suffering.

That’s not to say that you should flaunt your relative wealth. Part of good OPSEC is living as much like everyone else as possible. If you’re watering your lawn and washing your cars, while everyone else is fighting to have enough water to drink, it will quickly become obvious that you have an abundance of water.

You can expect that to be immediately followed by a line of people forming at your front door, expecting you to share with them.

However, one way of hiding your wealth might be to co-opt your neighbors. If you have enough water to share, then why not share it with them? Allow them to get their water from you, rather than having to go to the water point and stand in line. Just make sure you know how much water you are able to produce and how much you can afford to give them.

Sharing your water with your neighbors could act to help protect you, as they would have a vested interest in your source of water remaining a secret. That has some real tactical advantages, especially since it will be much easier to co-opt their cooperation, than trying to hide what you’re doing from them.

Unless your OPSEC is perfect, you have to assume that your neighbors at least have some idea of what you’re doing.

Finally, whatever you do, don’t panic. Panicking will just make it more difficult to survive. Nobody can think clearly when they are in panic mode. But there’s really no reason for you to panic. You’re the one who knows what to do and has prepared to do it.

So, while everyone else is worried about how they’re going to survive, you don’t have to worry. All you have to do is put your plans into action and keep going forward. You’ll be all right.

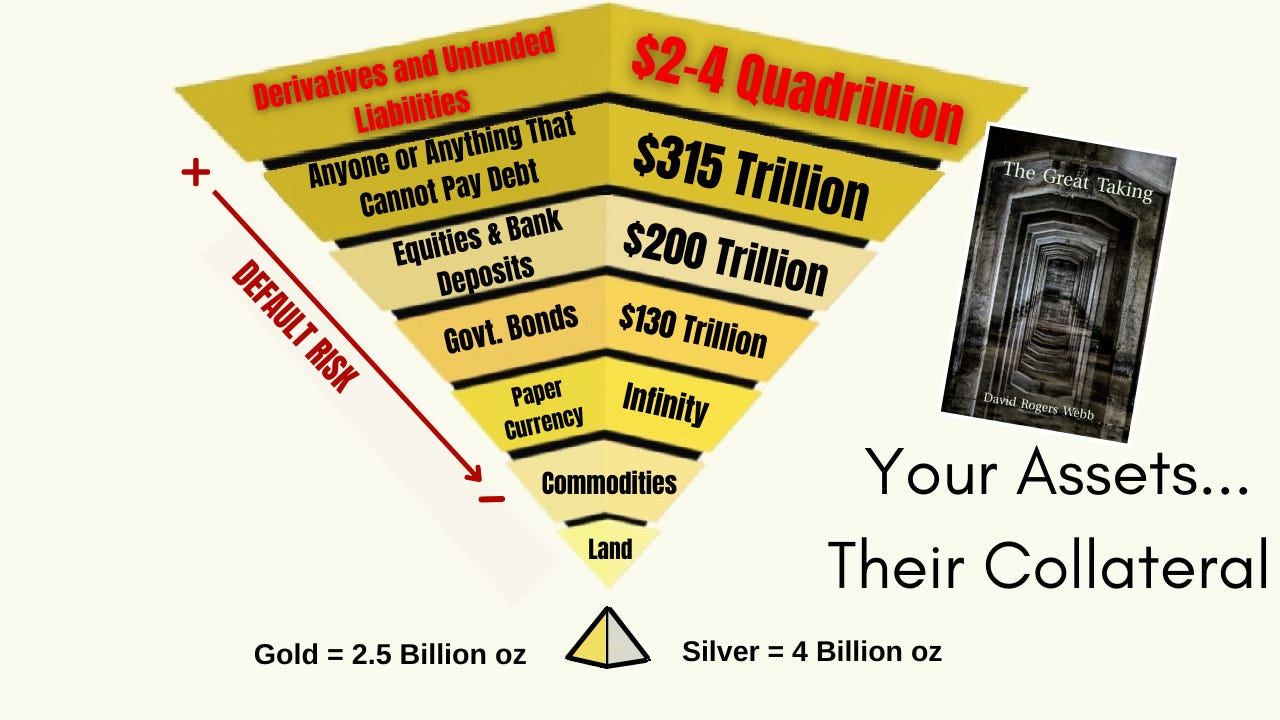

The biggest criticism of David’s book, The Great Taking, was that it offered no solutions. While it lays out the problem with expert precision—thoroughly unsettling the reader in the process—it never reached the natural next step: “And here is what you can do about it.” For many, that omission was a bitter pill to swallow. They wanted a step-by-step guide on how to protect themselves and their families from the coming flood. But no life jacket was provided.

Having become friends with David over the past three years, I understand that the absence of proposed solutions was neither an oversight nor an attempt to simply blackpill the reader. Rather, it reflects his sincere belief that something this vast and this evil cannot be fully defended against. Even if one manages to escape the first wave of confiscation and the Great Taking itself, it will be followed up with others—each designed to ensnare those who evaded the last. This is not hypothetical. History offers countless examples in which, after the majority has been impoverished, the remaining pockets of wealth are inevitably targeted.

The most egregious expropriation of wealth rarely appears at the outset of a crisis. It emerges at the end—after society has already been broken and reset. In Communist Russia, the revolution and the murder of the Romanov dynasty came first. Economic collapse followed, then years of scarcity and impoverishment. Only once the masses were fully crushed, having already lost most of what they owned, were the remaining productive classes targeted. A population rendered desperate was easily mobilised to justify the seizure of land, businesses, and assets.

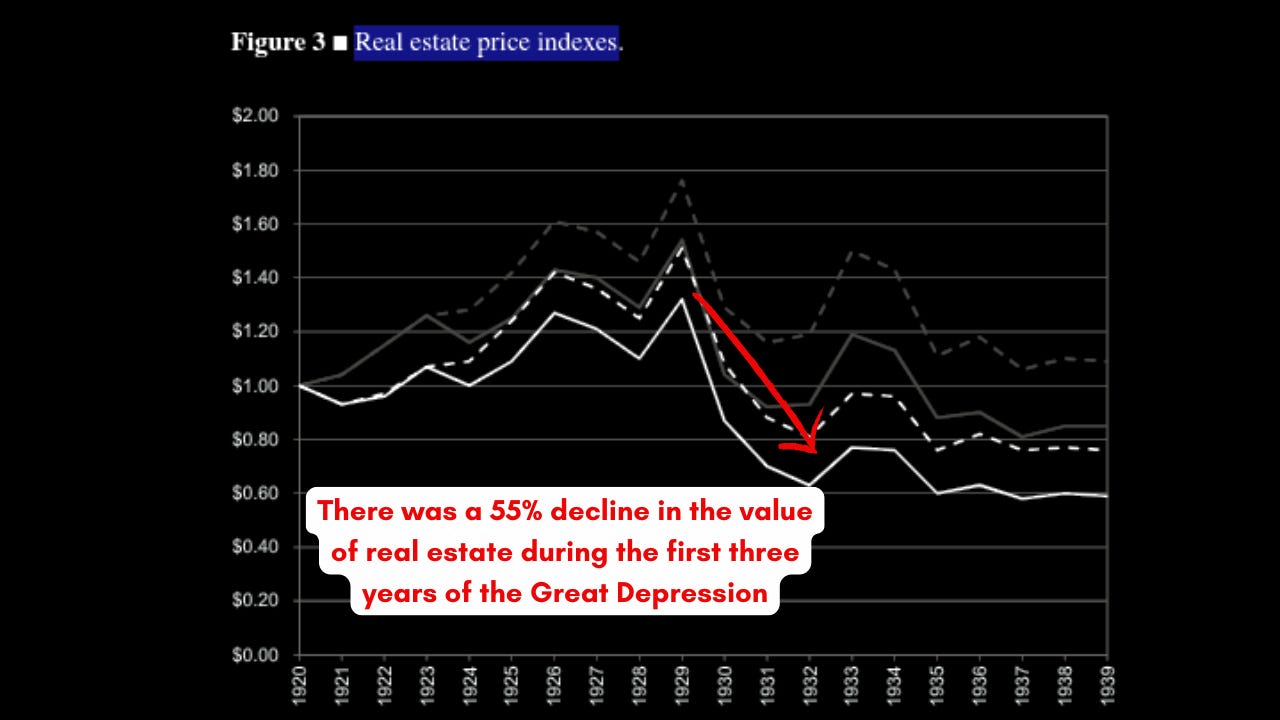

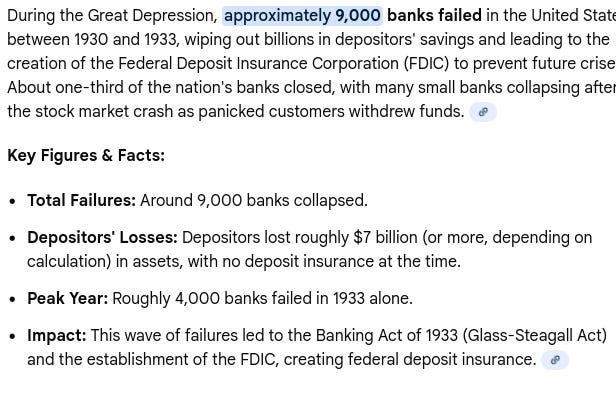

A similar pattern unfolded during the Great Depression. It began with the stock market collapse, which triggered a cascading credit contraction and the failure of banks across the country. Depositors saw their savings wiped out as institutions closed their doors. With the banking system in chaos, credit froze, collateral values collapsed, and industrial activity ground to a halt. Millions were thrown out of work. Mortgages fell into delinquency en-masse and many citizens wound up losing their family farms to the big banks.

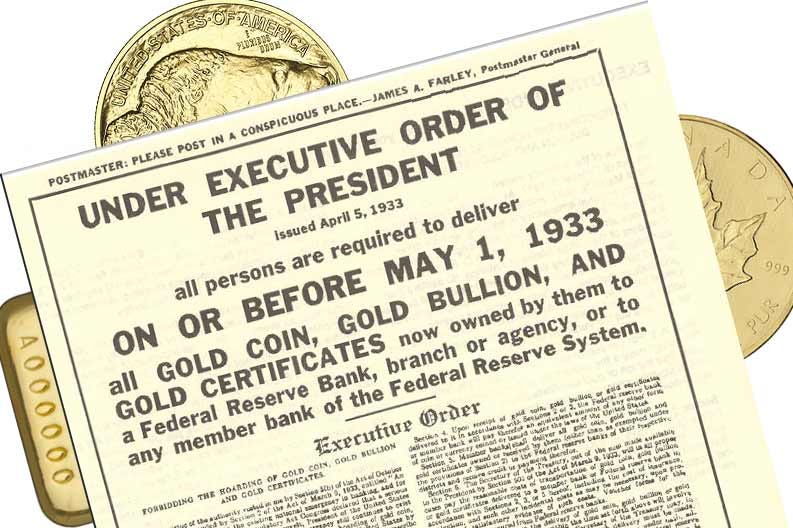

With no access to refinancing, even solvent families were losing their properties. For those who managed to survive, physical gold coins held outside the banking system, appeared to be the natural place to store what remained of their wealth. Or so they thought. Once again, after society had been sufficiently weakened, the state moved against the survivors. The gold holders. Those who believed they had escaped the asset seizure were quickly brought back to reality.

If you want to understand what happens during a systemic unwind, this is the blueprint. First, the credit system fails. Next, assets are liquidated or seized through refinancing failure—or through mechanisms like the Great Taking. Finally, whatever wealth remains outside the system is targeted and pulled back in. With asset tokenization and digital IDs on the near horizon, it is not difficult to imagine that physical and unregistered wealth—sitting beyond institutional control—could be targeted in the near future.

These mass looting events are never straightforward. The narratives are layered, distorted, and deliberately opaque, ensuring that most people neither see what is coming nor understand what is happening until it is far too late. Some may even participate in the confiscation of other citizens’ wealth, genuinely believing they are advancing a form of social justice.

With so many young people ideologically captured—and simultaneously locked out of housing, without any realistic path to prosperity—is it really unthinkable that a portion of them could be radicalized into supporting, or even participating in, the expropriation of property from so-called “selfish boomers”? When surveyed, over 50% of young people in America—the most free nation on earth, with the strongest property rights ever established—already support wealth redistribution! It is not absurd to imagine that a small fraction of them could be pushed toward violent action if it were sanctioned, justified, or encouraged by the state.

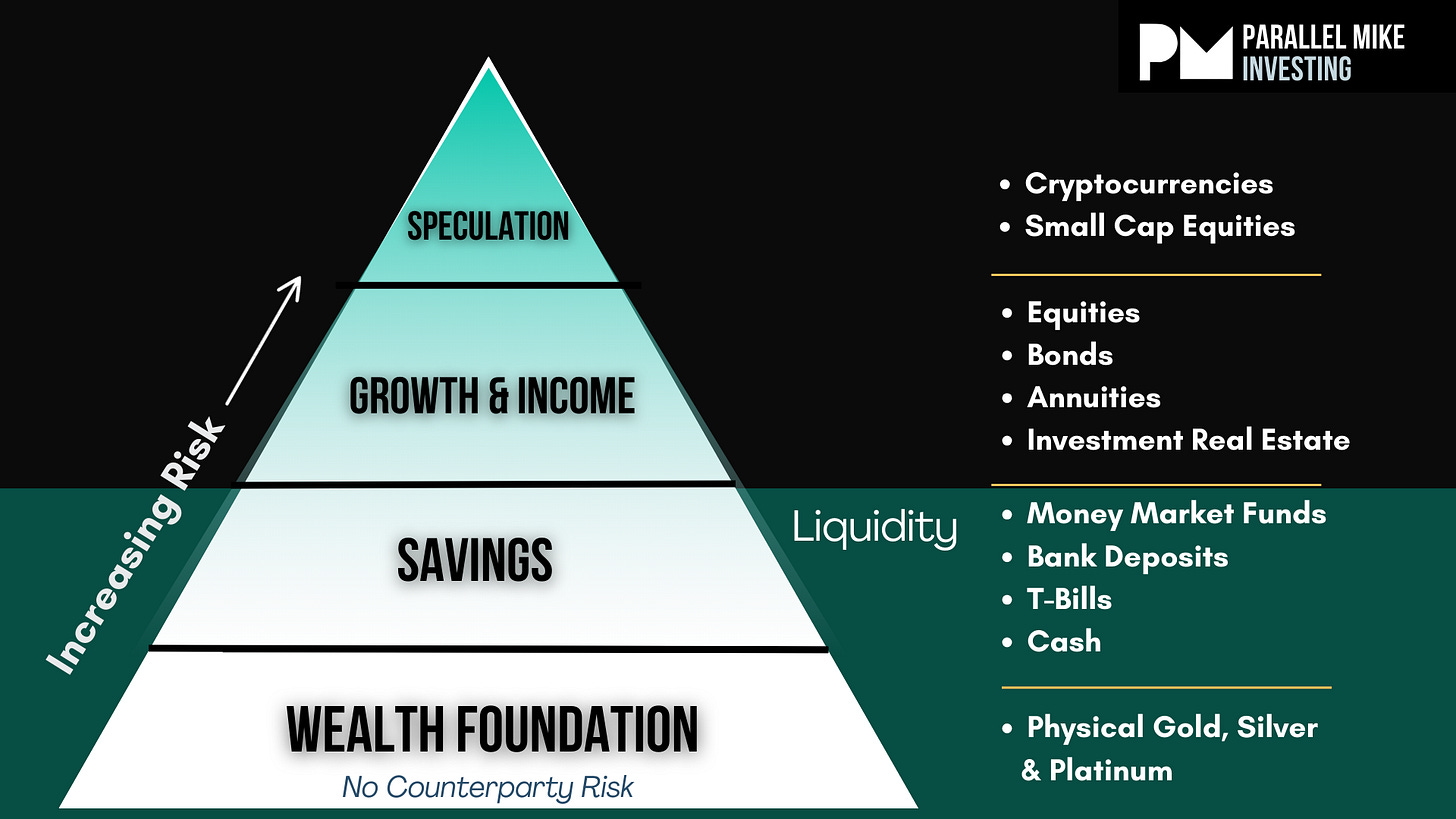

For all these reasons, any serious discussion about protection from something like the Great Taking is inherently complex. It must go far beyond simplistic advice such as “just buy gold.” The real threat is not isolated confiscation, but a full-spectrum breakdown: counterparty failures, collapsing collateral chains, evaporating liquidity, and the shutdown of the very channels through which assets are normally transferred or sold—followed by societal implosion and a rising tide of anger, fear, and despair.

In such an environment, survival is not about beating the system—it is about not being swallowed by it. The Great Depression shows us that when the collapse reaches its bottom, they come not only for the vulnerable, but for the last remaining stores of independent wealth. David, as a lifelong student of the Great Depression, understood this well. He knew that any attempt to lay out a solution in his book would be a) woefully inadequate b) give people a false sense of security and c) reduce the likelihood they would feel compelled to push back against the Great Taking in more meaningful ways.

My point is, the idea there is a perfect, simple solution to this kind of risk must be dispelled. There is no single hedge against systemic collapse, only a maze of vulnerabilities and risks to try and deal with. Protecting your family against the Great Taking requires a fundamental shift in both mindset and lifestyle. That’s why I’m writing this from a homestead, where my family and I take responsibility for our own food, water, and energy, as much as possible. I am surrounded by other farms, each with its own fresh water supply, off-grid heating, and food production. It’s no coincidence that David Rogers Webb has chosen a similar way of life, as did Matt Smith @ Crisis Investing and Doug Casey, two of the other early voices who helped raise awareness of the Great Taking.

Put simply, those of us who truly understand the risks before us—and what is likely to follow when the financial system finally unravels—are taking serious preventative steps. We recognize that living in dense urban environments while remaining dependent on centralized systems is a terrible idea. We know we need to be out of the cities and at least semi-self-sufficient. The fact that each of us made significant sacrifices to prepare for that future should be instructive in itself. The truth is, we don’t know how bad it could get. But history is very clear on one point: when debt bubbles burst and old systems die—and that is precisely where we are in the cycle—things become chaotic very, very quickly.

If this all sounds like too much effort—and you were hoping for a simple, easy-to-implement answer to the question “How do I prepare for the Great Taking?”—then unfortunately, you’re going to leave this article disappointed.

Real solutions to substantial and complex problems are never easy. They demand:

There are no shortcuts here. When it comes to the Great Taking, no amount of clever portfolio restructuring will work if you have not first secured your most basic requirements for survival. History is unequivocal on this point. People endure hard times by minimizing their dependence on centralized systems. That means developing:

Believing you can protect your wealth while being unable to feed yourself without a supermarket is dangerously naive. And that naivety is precisely what the system relies on. Always remember—those who would like to see you property-less and dependent are always thinking several moves ahead. You need to think several moves ahead +1.

What you’re about to read are, of course, only my opinions—but I hold them firmly. There are no shortcuts to achieving a meaningful level of protection, so I won’t pull any punches. If I’m going to attempt the impossible—by addressing something even David chose not to tackle directly in his book—I will do so honestly.

We are living through an exceptionally dangerous period in history. Navigating it successfully requires both a realistic understanding of the risks before us and right intention: the desire and courage to act decisively, even when certainty is impossible. Without this, my article will be of little use. But for those prepared to take action, there is an opportunity not just to survive the hard times ahead, but to thrive during them. That is my goal—and I invite you to join me on this journey.

For those willing to face this reality head-on—who want genuine resilience and meaningful insulation from what’s coming—read on.

Whether the catalyst is the Great Taking itself, or the inevitable collapse of the everything bubble, the framework I’m about to share offers the strongest protection realistically available to us

Just please be aware, it is:

So, with that said, let’s get to it.

I was recently in a Wealth Preservation Consultation discussing the Great Taking with a client, and I used the following analogy: the global financial system is like a massive, decadent casino. You go inside, and everything looks and feels opulent and secure. You’re made to feel at home, with the hope that you forget you’re in a casino at all. So you stay, and never cash out.

Most of what you consider to be your “wealth”—stocks, bonds, retirement accounts, digital assets—are actually just chips you’re told possess real value. They feel real, and for a while, it seems like you own some of them. But the reality is, those chips are an illusion. The real wealth sits in the cashier’s booth, controlled entirely by the house.

Obviously the owners of the casino are well aware that it’s about to go bust—and if this happens, the rules suddenly change—and you lose it all. The chips in your hand transform from claims to real value, to nothing but redundant plastic tokens. They are worthless if you haven’t converted them into something real before the collapse. Meanwhile, all of the actual wealth that was stored in the cashiers booth disappears in an instant, taken by the casino’s owners.

Oh, and as you’re leaving, they decide to take your wallet — and the watch on your wrist too — because everything in the casino belongs to the casino. It’s only at that moment you realize the whole place was a scam, run by the mafia all along. But it’s too late. You walk out with nothing. This is a very apt comparison for the financial system. That’s not to say the casino can’t be profitable while the doors are still open — but you must recognize that it is a casino. And to survive its inevitable bankruptcy, you have to be willing to step outside its cozy confines.

When you realize the aforementioned, action becomes unavoidable. This is where my Citadel Strategy comes in. A citadel is more than a fortress—it is the last stronghold, the final bastion of security when everything else has fallen. Historically, it was the heart of a city’s defences, built to protect people and vital resources through prolonged siege. In the context of the Great Taking, the Citadel Strategy serves the same purpose.

It is a deliberately layered set of defences — mental, physical, financial, and social — designed to protect you and your family, so that even a sustained attempt to seize your wealth or push you into dependency is unlikely to succeed. If the outer layers fail or turn hostile, the next layer rises, and the next, each adding complexity and resilience, ensuring that the inner stronghold—completely self-sustaining and independent of the other layers—remains untouched.

The idea is to build multiple layers of protection, insulation and redundancies into your life, both financial and otherwise, to ensure you and your family are able to survive the most challenging of circumstances. It’s your roadmap for walking out of the casino, and into a more meaningful, and prosperous future, before the house comes to take it all. It’s about converting your casino chips into real, tangible assets you hold in your own possession. It’s about building a life where you don’t need the casino to survive, and instead, you’re surrounded by loved ones, community and real wealth. Then having the strategies and mindset to hold onto it. This is how I personally am preparing for the hard times ahead, including the Great Taking. For what it’s worth, I walk the walk, and everything I describe below—is what me and my family are already doing.

Ring 0: The Inner Keep – The Sovereign Mindset – Cultivate radical personal responsibility and mental resilience; recognize that debt is a primary tool of control and commit to breaking its shackles.

Ring 1: The Physical Bastion – The Unassailable Homestead – Build a debt-free, off-grid homestead surrounded by productive assets that provide food, energy, water, and income. This will give you complete independence from the system.

Ring 2: The Treasury – The Ark of Real Value – Hold portable, physical wealth in precious metals, held securely and compartmentalized, beyond the reach of confiscation.

Ring 3: The Liquid Veins – The River of Cash – Maintain cash reserves in diversified currencies to navigate immediate and medium-term crises.

Ring 4: The Web of Influence – The Network of Reciprocity – Build trusted family and community networks for mutual aid, barter, and collective resilience.

Ring 5: The Outer Shadow – The Legal and Jurisdictional Moat – Use legal, geographic, and structural strategies to shield assets and create asymmetric protection from asset seizure.

This is the foundation of the Citadel Strategy. Before buying a single ounce of silver or an acre of land, you must secure the “Inner Keep”—your own mind. This is the psychological fortress where you deprogram yourself from reliance on a system that plans to dispossess you. It is about moving from dependency to radical personal responsibility.

The system’s greatest weapon is normalcy bias—the tendency to assume tomorrow will look like today. This bias blinds people to incrementalism: the deliberate, step-by-step erosion of freedom, security, and wealth. Each new regulation, cost increase, or loss of rights may seem minor on its own, but over time these small changes accumulate, steering people toward eventual annihilation. Even shocks that should provoke outrage—like the mass poisoning of family and friends during Covid or the revelations and gaslighting surrounding the Epstein files—are gradually reframed and normalized, reinforcing the illusion that all is “normal.” But what is happening isn’t normal—it’s deeply disturbing.

This realization should not paralyze you with fear. On the contrary, it should ignite action. Falling into despair, or convincing yourself that there is no hope, is itself part of the psychological operation designed to neutralize you. You must reject it. The correct response is to seize your agency—to recognize that you are responsible for your own survival, security, and future, and to act accordingly.

Seizing your agency means moving from victim to architect. It means accepting that nobody is coming to save you—and that you alone are responsible for your success or failure in life. This shift in mindset is deeply empowering. It moves you from passive dependence to active participant, and enables you to build a life resilient to shocks of all kinds, including the Great Taking. When you do this, you become sovereign, as our creator intended.

To strengthen the Inner Keep, we need to cultivate what I call a “Depression-Era attitude.” This is the mindset of the generation that survived the Great Depression—grounded in practical resilience and real-world self-reliance. We can break it down into the three R’s:

The Inner Keep—fortified with a sovereign mindset and a Depression-Era attitude—is the bedrock of the entire Citadel. Every other fortification depends on it. Without Ring 0, you are unlikely to succeed in protecting your family’s wealth, and quality of life. It is what allows you to see clearly, act decisively, and take full responsibility for your future. The good news is that once you build out the inner keep, it cannot be taken from you. It is the one asset that is truly immune to confiscation.

Before you can build a Citadel, you must first ensure you are not standing on quicksand. The most dangerous vulnerability in the face of the Great Taking is debt. You must understand this clearly: If you have debt, you do not own your assets. If you have a mortgage, the bank owns your home; you are merely a tenant with a liability. If you have a car loan, the dealership owns the vehicle. In a systemic collapse or a Great Taking type event, debt is the primary lever used to strip wealth from the population. This is something David has mentioned many times in interviews.

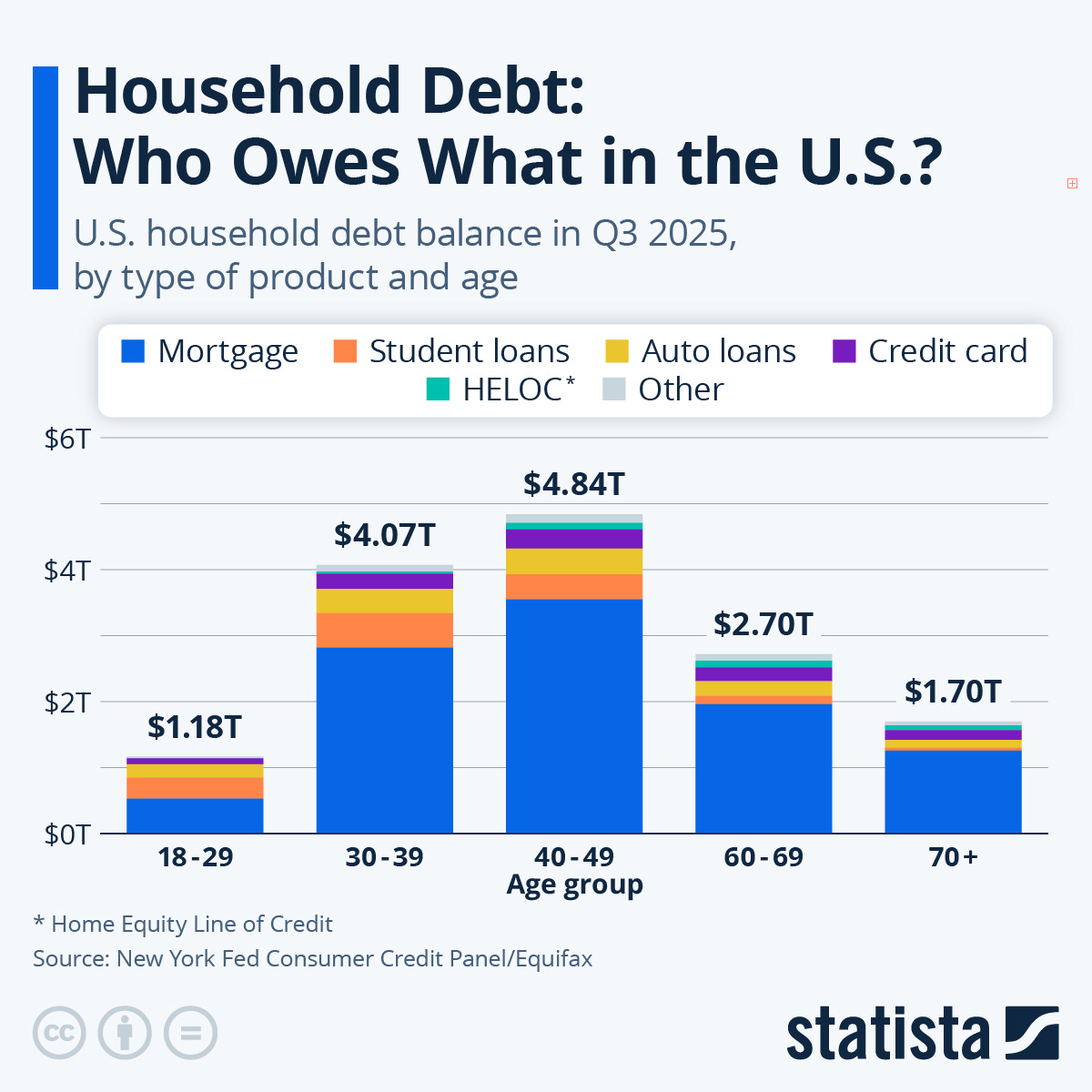

In a deflationary collapse—which often precedes or accompanies these resets—asset prices collapse, wages vanish, and both credit and liquidity dries up. However, the nominal value of your debt remains fixed. You could find yourself owing $500,000 on a home that is suddenly worth $100,000, while your income has been cut in half, or lost entirely. This was the trap during the Great Depression that allowed institutions to foreclose on millions of properties, transferring real assets (land and housing) from the people to the banks for pennies on the dollar. At the height of the Great Depression unemployment was over 25% and over 60% of all mortgages were in delinquency. Over 1000 properties per day were being foreclosed on. I expect these numbers could be eclipsed in the coming downturn.

For these reasons, the ruthless elimination of all debt—consumer, vehicle, and especially mortgage—is not just a financial goal; it is a prerequisite to financial and spiritual sovereignty. You cannot be sovereign if you are in bondage to the very system you are trying to protect yourself against. Pay it off, downsize, or sell the asset to clear the note. Better to live smaller in a debt free property that is truly yours, than in a mansion or large acreage that belongs to the bank. So beyond developing a sovereign mindset, step number one financially speaking, is to break the shackles of debt.

Now let’s move on to the five outer rings.

The most important protection against systemic collapse and the Great Taking is what I call the Unassailable Homestead. In a fragile future, a homestead is far more than a place to live — it is the foundation of your families security and resilience, and a space you can truly thrive. If everything else fails, it keeps you safe, allows you to meet your basic needs, and supports both mental and physical wellbeing. Over the long term, it also reduces costs, can generate income, and insulates you from financial shocks by removing your dependence on volatile energy and food prices.

History shows its importance. During the Great Depression, the key factor determining whether someone survived or ended up in a soup line was their exposure to debt and their immediate living situation. Farmers who owned their land outright generally survived with relative ease. When the credit system failed, unemployment spiked, and cash became scarce, they were largely unaffected—they could provide for themselves in-house. Fortunately for us, natures abundance doesn’t follow the business cycle.

Worth pointing out, the modern way of living, now ubiquitous in the West, is a complete historical aberration. Our ancestors rightly built layers of insulation during the good times knowing that hardship was always one crisis away. Waiting until hardship arrives means you’ve already missed the boat. By then, it’s too late. This is why you should aspire to build your Unassailable Homestead as soon as possible. It should be debt-free, have off-grid solutions, be located away from major urban centers, and ideally surrounded by like-minded, self-reliant neighbors. This creates many layers of additional protection in terms of food, water, and security, while offering a marketplace right there on your doorstop for trade and barter, should a crisis suddenly emerge.

It doesn’t need to be an all-singing, all-dancing farm. Simply owning land where you can grow food and practice self-reliance is enough. For those with less capital, living in a camper, trailer, or tiny house for a year or two to secure the land is often worth the sacrifice. I speak from experience: I lived on an 8-meter boat for five years to save money and eventually buy my homestead debt-free.

For many, this represents a radical departure from their previous life. But if real peace of mind is the goal, this is how it is built. Right now, we are in the midst of a major property bubble in the West. When it bursts, residential real estate values will collapse. At the moment, there is still an opportunity to sell these overvalued ‘assets’ (soon to be liabilities) and use the proceeds to acquire property that will truly serve your needs in a crisis — the kind of property that becomes far more desirable, not less, when SHTF.

This kind of property is more than a home; it’s a base for your family and your real-world assets. Our great-grandparents didn’t own stocks or NFTs. They invested in themselves and their farms. Just think how wild it is that today, millions of people have seven digit brokerage accounts and yet have no way to feed themselves or survive a cold winter without centralized systems. They are nominally wealthy, but in practical terms, they are poorer than poor.

When a real-world crisis strikes, be that the Great Taking or some other major systemic shock, the humble farmer will outlast them — both financially and practically. Our great grandparents would have never put themselves in such a sad position. They understood that the family homestead, was not only their primary investment, but their primary means of survival. They never expected big daddy government to keep them. The idea would have been absurd. It’s a stark reminder of just how dependent—and psychologically backward—we’ve become. The Unassailable Homestead fixes that.

Developing a homestead is one of the most practical ways to grow real, tangible wealth. Over the coming decade, demand for properties like this is only going to increase. At the same time, supply will collapse as prices skyrocket and more people rush to get out of the cities.

Any improvements you make along the way directly increase the value of the land. Things like:

Similarly, I also recommend land in general as an investment. This could be parcels of land or forestry separate from your main dwelling, held for capital appreciation and to provide you with additional resources. Unlike most assets, land is largely uncorrelated with the stock market and tends to move more in line with gold. In my opinion, at some point land will become nearly impossible for regular people to buy—as the elites are snatching it all up, which tells us something important. Securing some now is vital!

Of course, land is also inherently Great-Taking-proof. Owning it outright ensures it cannot be collateralized in any way. A smart strategy is to invest in land close-by—within about 45 minutes of your main property. This creates a secondary asset that’s close enough to manage, yet completely separate from your primary homestead. If you ever decide to sell it, you can do so without affecting your main property, making it a fully independent asset.

When you choose to go back to the land, particularly if you spent your life living in the city, expect some opposition from friends and family who don’t see what you see. Going against the grain always provokes pushback. My wife and I experienced the exact same thing. A true contrarian knows this is a good sign; siding with the crowd during these periods of history is almost always a terrible decision. Similarly, doomers will tell you, “It’s pointless; they’ll send drone swarms to kill you and seize your homestead,” or “good luck when the roving mobs come to loot you.” These people are irrelevant and destined to be the first to fall.

They don’t have a sovereign mindset—they have a slave mindset. The battle has barely begun, and they’ve already surrendered. Worse, they are actively seeking to poison others, and deter you from taking action. That is unforgivable. We know the risks; our task is to find solutions. But for these people, your action is threatening—because it holds a mirror to their cowardice or laziness.

I suggest reducing your exposure to these kinds of people as much as possible. When these people appear in my comments section, it’s an instant block. They don’t want to be helped, only to deride those who are taking action to make themselves feel better about their own inaction. It’s about as bad a take as you could have. There has never been a point in history where taking preventative action didn’t make sense and increase a person’s chances of success.

Yes, there are no guarantees, and there is every chance that a true tyranny will turn its attention to the survivors also—I covered this in my introduction, but the future is not a foregone conclusion. Irrespective of what happens, building your Citadel will give you and your family far more health, happiness, and opportunity, than you would otherwise have had. Meanwhile, Mr. Doomer will be shipped off to the nearest 5-minute city at the first sign of trouble — having lost it all because “there was no point in preparing” and thus, he was left with no other option.

This ring is the repository of your portable wealth. It is designed to survive the collapse of the fiat currency system and serve as the foundation for a new one. To understand why this ring is necessary, we must look at the inevitable destination of the current financial path. Everything we see is pointing to a financial reset. I was predicting this long before I knew about the Great Taking, and I remain steadfast in that opinion.

When you hold a physical gold/silver coin or bar in your hand, you possess the asset outright—it is not a promise to pay, it is value itself. This is the only asset class that exists entirely outside the digital ledger and the reach of a sudden default or confiscation. Right now, we are seeing a rush into precious metals as key financial players realize the massive default that is incoming. Take heed. It’s no surprise to me that since the Great Taking book was released, the gold price has more than doubled.

Gold (The Core): Physical gold is the ultimate long-term store of wealth, a role it has fulfilled for over five millennia. Unlike financial or digital assets, it cannot be defaulted on, wiped out in a fiscal crisis, destroyed by a cyberattack, or lost to a counterparty. This makes it the lowest-risk asset in the world, and yet, despite this, it has been the best-performing asset over the past 25 years.

As the financial system resets, it does so against gold, ensuring strong demand from central banks and wealthy families for decades to come. In the context of the Great Taking, the foundation of your wealth preservation must begin with gold. It is the bedrock of any portfolio—a principle you can explore further in my article on the Wealth Preservation Pyramid.

In order to maintain true flexibility and liquidity, you must diversify both the forms of gold you hold and their storage locations. Gold is the densest, most portable store of value—far easier to transport in a crisis than silver—making it the cornerstone of any robust Citadel strategy.

Silver (The Circulation): Silver is best viewed not as an investment, but as your day-to-day barter currency. Pre-1965 US 90% “junk silver” coins are ideal: universally recognized, easily divisible, and can be bought very close to spot. Supplement them with generic 1-ounce and 10-ounce rounds or bars. In a true crisis, silver becomes a practical payment mechanism to buy goods and services, giving you real liquidity and flexibility even when conventional money loses its value.

Platinum Group Metals (The Hedge): A smaller allocation (5-10%) to platinum and palladium, whilst not necessary, can provide diversification. These metals have significant industrial demand and often move somewhat independently of gold and silver, protecting you if one market is manipulated or suppressed, or a confiscation order makes our preferred metals illiquid for a period of time.

Before acquiring physical metals, it’s essential to obscure the trail that leads to them. This is a critical step in protecting your wealth from potential future confiscations. While gold and silver in your possession cannot be lost to the Great Taking, history shows they can still be targeted in subsequent waves of seizure.

While the ultimate goal is to move beyond fiat currency, the financial reset will almost certainly unfold in stages. During the phase when the system is stressed but not yet fully broken, physical cash remains king. But what happens if banks begin to fail or governments impose strict withdrawal limits, as happened to Greek citizens during the Eurozone crisis? Banks could deny access to your deposits, ATMs could go dark, and yet cash will still be essential to survive.

Be warned: Deposits held in the bank are not your own. It’s a loan unto the bank and therefore exposed to 100% loss and an eventual bank bail-in. Deposit insurance schemes are worthless and in a true crisis even solvent banks and well run credit unions are at risk. Many of them will have a target on their back given it will be the Federal Reserve system who picks the winners and losers.

Even without a full blown banking collapse, it’s becoming worryingly normal for bank accounts to be weaponized—just look at the Canadian truckers’ protest. Having some physical cash is one way to protect against this. While fiat currencies are clearly a terrible form of long-term wealth preservation, in the short to medium term, they remain critical for our day to day economic survival. History shows us that before people lose their assets—they first lose their liquidity. Those who maintain it, ensure they can buy essentials, avoid incurring debts, and travel, whilst those who failed to prepare are busy rioting outside shuttered banks.

For this reason, you should keep enough cash on hand to cover at least three months of expenses. For those preparing for a Great Taking scenario, a more comprehensive approach is the cash ladder.

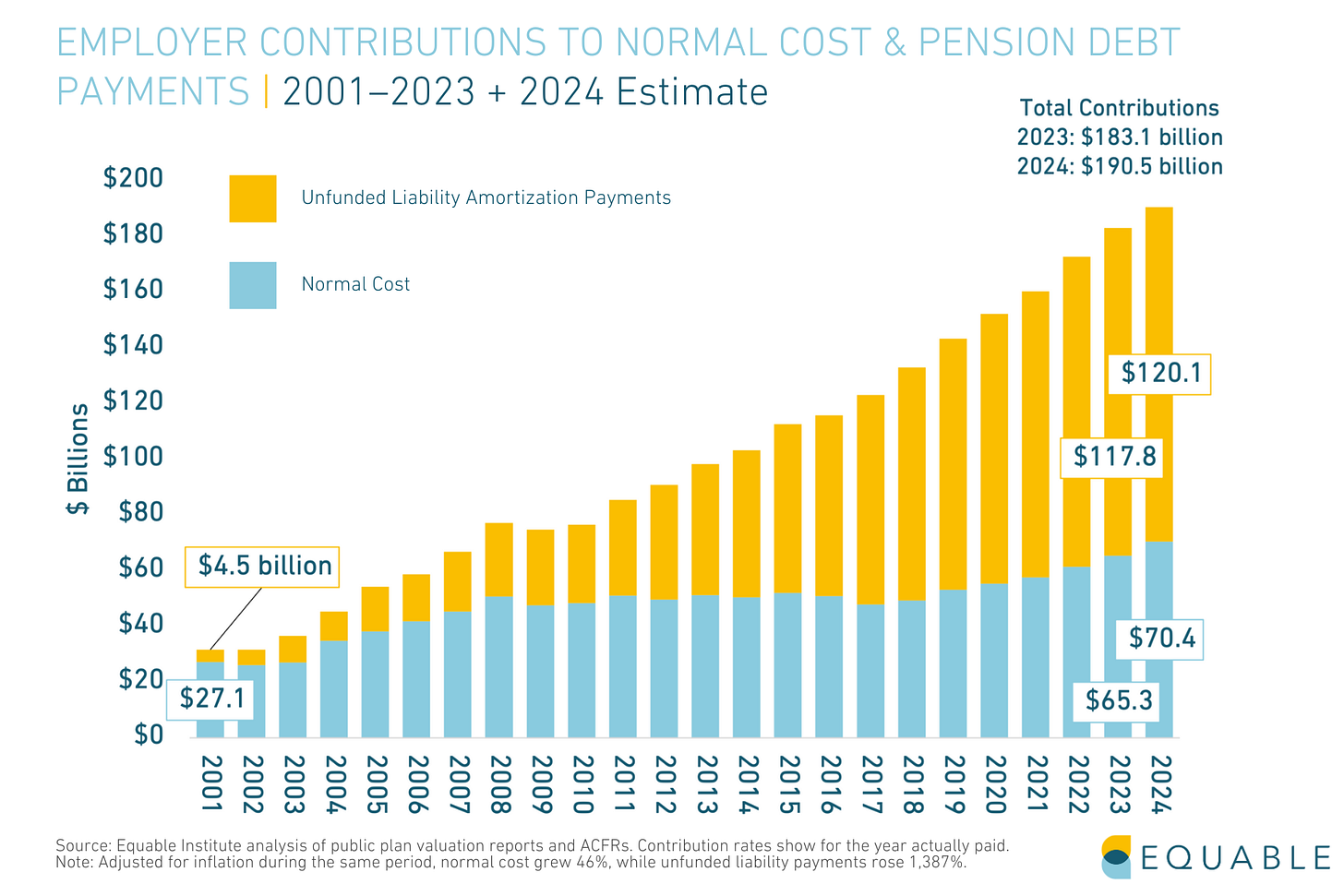

The short answer is yes, our retirement accounts are sitting ducks. One of the hardest conversations I have with clients is explaining that, regardless of whether the Great Taking occurs, their pension is extremely vulnerable to total loss. The entire system is structurally broken. Most pension funds are undercapitalized, fragile by design, and fundamentally unsustainable — hollow shells propped up by promises that cannot be kept. And this is before a major financial downturn has even begun!

At the same time, the stock market sits in a historic hyper-bubble, a ticking time bomb waiting to explode. Sovereign debt will be defaulted on — either through the silent theft of inflation or outright repudiation. Yet these two instruments, equities and government debt, form the backbone of most private pension schemes.

In the coming crisis, the vast majority of pension funds, 401(k)s, and retirement accounts will be annihilated. And if the Great Taking does occur, even the most pristine and well-capitalized funds will be seized, leaving beneficiaries with nothing. All of this will unfold alongside collapsing housing prices, banking crisis, and soaring unemployment. This may sound like a doomsday scenario, but that is actually the point. The dominoes have been deliberately arranged this way, so everything fails simultaneously. A controlled demolition that immediately eviscerates the wealth of most citizens.

Of course, for those who have spent a lifetime paying into these systems — and who have spent decades psychologically investing into the illusion that their retirement account will be there and provide security in old age — this is a bitter pill to swallow. The instinctive response is often denial: “But my fund is different…they assure me my fund is safe.” You must resist the temptation of self-delusion.

It goes without saying that government pensions are dead in the water. Our nations are already insolvent. Future payouts will likely devolve into a form of conditional UBI — subsistence-level support tied to behavioral compliance. Anything controlled by government will be used to control you. Period.

Ok, so now we have had our reality check, what can we do about it?

Firstly, for those who can access their pension early, why wait? Keeping it in the fund, ensures it remains vulnerable to all of the above. For those unable to fully liquidate their accounts and convert them into real-world assets, establishing a self-invested personal pension (SIPP) or a self-directed IRA is the next best option. This provides far greater control over the underlying assets. In many jurisdictions, pension funds can be allocated into vaulted metals held in your own name — offering the best chance of preserving both your retirement savings and the assets themselves when the music stops.

Wealth is not just what you own, but who you are connected to. In a true systemic crisis, the financial system will freeze, institutions will fail, and the atomized, isolated individual will be helpless. An unassailable homestead and layers of liquidity will ensure your immediate survival, but longer term, you need a network of trusted, capable individuals. A community. This is your most powerful and enduring defence—one that cannot be confiscated, frozen, or devalued by any central authority.

The atomization of modern society did not happen by accident. Over the past century, powerful forces have systematically dismantled the multi-generational family. Children move far from their parents for careers — having been indoctrinated by electronic devices and public schooling. Grandparents are warehoused in nursing homes — desperate institutions designed to drain a lifetime of accumulated wealth before death, ensuring nothing is passed down.

The nuclear family itself has fractured into isolated individuals, each dependent on the system for needs once met by kin. This is not progress; it is a control mechanism. An isolated individual is easy to manage and easy to dispossess. They know this, which is why the scamdemic was so successful. It’s much more difficult to take everything from a man surrounded by three generations of loyal kin; even harder if he has an entire community behind him willing to help protect his property and rights.

A key protection from future hardships is, therefore, rebuilding family bonds. Reconcile with your children or parents. Strengthen bonds with siblings. Consider a return to inter-generational living — where grandparents provide wisdom and childcare, adult children contribute labor, and elders are cared for at home, not abandoned to institutions that quickly consume their estates.

Beyond economics, this rebuilding creates meaning—the profound purpose that comes from sacrifice for those who came before you and those who will come after. The joy of living with grandchildren, the wisdom of elders, the shared pride in building something that outlasts you all. It is your loving connections — not your money — that they want to loot from you the most. A family, rebuilt and united, is the ultimate act of defiance in the modern world—and the best protection against despair and isolation.

Beyond family, you can begin to build alliances within your broader community. Consider local churches, neighbors, and anyone living a similar lifestyle of self-reliance. Reach out. Make connections. Become a resource by buying directly from them—their eggs, their produce, their services. Find ways to offer something of value back to your community, whether skills, labor, or goods from your own surplus.

This is not merely about preparing for crisis; it is about building a network of trusted individuals you can turn to for support. History proves that a unified community is extremely difficult to dispossess. In communist Eastern Europe, the Soviet system crushed individuals and isolated families with ease, but they had no answer for the Polish farmers. Despite decades of pressure, collectivization failed in Poland because the farming communities were too numerous, too interconnected, and too stubborn to break. There were simply too many of them, bound together by shared faith, culture, and mutual dependence.

During the Great Depression, many farmers rallied around neighbors who had fallen behind on their mortgage payments, and ensured auctions of foreclosed went no bid. So families about to lose their homes could buy it back at the lowest price possible. A community rooted in genuine relationships and economic interdependence becomes a fortress that no central authority can breach. This is also where your trade and barter economy comes in. The real ‘real economy’ during a systemic crisis.

As trust deepens, consider formalizing arrangements with your closest allies—3-5 families with complementary skills: medical knowledge, security experience, mechanical ability, agricultural expertise. Draft a plan covering mutual defence, resource sharing, and communication plans—for a worst case scenario. Meet regularly to strengthen bonds. The trust built over shared meals and honest labor is the glue that holds a community together when the pressure comes.

Whilst building real world community is imperative, it can take time. The internet allows you to connect with like-minded people worldwide with ease. People who are already building their own Citadels who you can learn from. Cultivate this network now. A global network becomes an important intelligence asset—alerting you to developments across jurisdictions, warning of threats, and potentially offering refuge or partnership.

This is the final ring of defense. It leverages legal and geographic strategies, turning the system’s own complexity against itself. Some of these strategies are more complex, costly, or require professional guidance, and may not be feasible for everyone. As the outermost layer, they are less critical than the inner defenses, but they are still worth considering.

The core mechanism of the Great Taking is the legal transformation of ownership into mere “securities entitlement”—a contractual claim that places you behind secured creditors. The solution is to demand physical paper stock certificates. This removes your shares from the DTC or Euroclear system and gives you back direct ownership, bypassing the Great Taking mechanism for equities.

Maintaining a small portfolio of investments within the traditional system can have advantages even in-spite of the Great Taking. This serves two purposes:

Minimize your long-term digital footprint. Use VPNs, privacy-respecting browsers, and encrypted email. This will help keep you invisible to the system ahead of any future wealth confiscations. Your public facing digital identity should be bland, ensuring your real wealth remains as invisible to the system as possible.

Establish accounts with non-bank vaulting firms in jurisdictions with strong financial privacy—the Cayman Islands, Switzerland, Austria, Panama, or Singapore. These firms are less likely to be subject to “bail-in” laws. Your gold in a private vault in Zurich is not subject to an executive order signed in Washington.

It’s possible to create a Foreign Asset Protection Trust (FAPT) in the Cook Islands or Nevis, or a Nevis LLC. These entities are designed to be extremely difficult and costly for foreign courts to pierce. An asset held by a properly structured Nevis LLC is shielded by a legal and geographic moat that would require years of litigation to breach—making it not worth the effort.

For those with sufficient assets, private banks in Switzerland, Liechtenstein, or Singapore operate under different legal frameworks than retail banks, offering greater privacy.

Consider a secondary property within a completely different jurisdictional profile from your primary homestead—a place to retreat if, for any reason, Plan A becomes untenable. Having multiple residences can ensure you have a place to escape to, as a last resort, if you need to leave your home country.

What I’ve outlined here is only the first step — albeit a substantial one. I’ve focused on the most vital components for obvious reasons; this article is already something of a tome. But risk management is an ongoing process, not a one-time event. The future is unpredictable, and there is no permanently safe position. Unfortunately, most financial advisors and wealth managers are simply not aware of the kinds of risks we are now facing. So we must become competent in protecting and managing our own wealth. Nobody else should be trusted to do this for you.

Twice a year I facilitate Group Coaching for Investors where I support people to learn the same wealth preservation skills and strategies I am using to protect and grow my family’s wealth, going into the reset. For those who would like to join us, our next group begins at the end of February.

As we move into harder times, the goal is not to fight the system head-on—that is a battle you will almost certainly lose. The goal is to defend ourselves against it, by becoming sovereign and resilient. If the Great Taking ensues, the system is engineered to take what is easiest to seize: digital accounts, brokerage portfolios, domestic vaults, mortgaged property, and pension funds or 401(k)s—all of which are neatly catalogued and trapped within the system. At this stage, it’s unlikely we can stop them, but your Citadel, deliberately built across all five rings and standing in the shadows, remains far beyond their reach.

For many, achieving even half of what I have outlined will be a serious undertaking. The good news is many people have already conquered this mountain. There is a tried and tested route, I speak from experience, given I have played the role of mountain guide for many. Whilst the Great Taking would be a catastrophe, we cannot say for certain if, or when, it will occur. What is certain, historically speaking, are cyclical downturns that bring real hardship. Stock market and housing market bubbles will eventually burst. Fiat currencies cannot last forever. Economic depressions are guaranteed in a debt-based system. These are not hypotheticals, but inevitabilities. We are seeing warning signs that all of them are potentially on the immediate horizon.

Personally, I don’t see this path as a sacrifice; I see it as a gift. Moving to a homestead and reducing dependence on systems that no longer serve us—if they ever did—is something to celebrate. Everybody I know who has taken this path is healthier, happier, and living a more meaningful life then they once did. These are the rewards that come from exiting the casino, and returning to what’s real. A genuine alternative. A future worth fighting for. For those who made it this far, I’ll close with a simple truth:

“The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second-best time is now.”

Take meaningful action, and build a life that allows you to thrive.

On December 17th, 2025, four witnesses testified before a joint session of House Homeland Security subcommittees about something that actually happened: a Chinese Communist Party-sponsored group used Anthropic’s Claude to conduct largely autonomous cyber espionage against approximately 30 US targets.

The witnesses included Logan Graham from Anthropic’s frontier red team, Royal Hansen from Google’s security engineering organization, Eddie Zervigon from Quantum Exchange, and Michael Coates, the former Twitter CISO now running a cybersecurity venture fund.

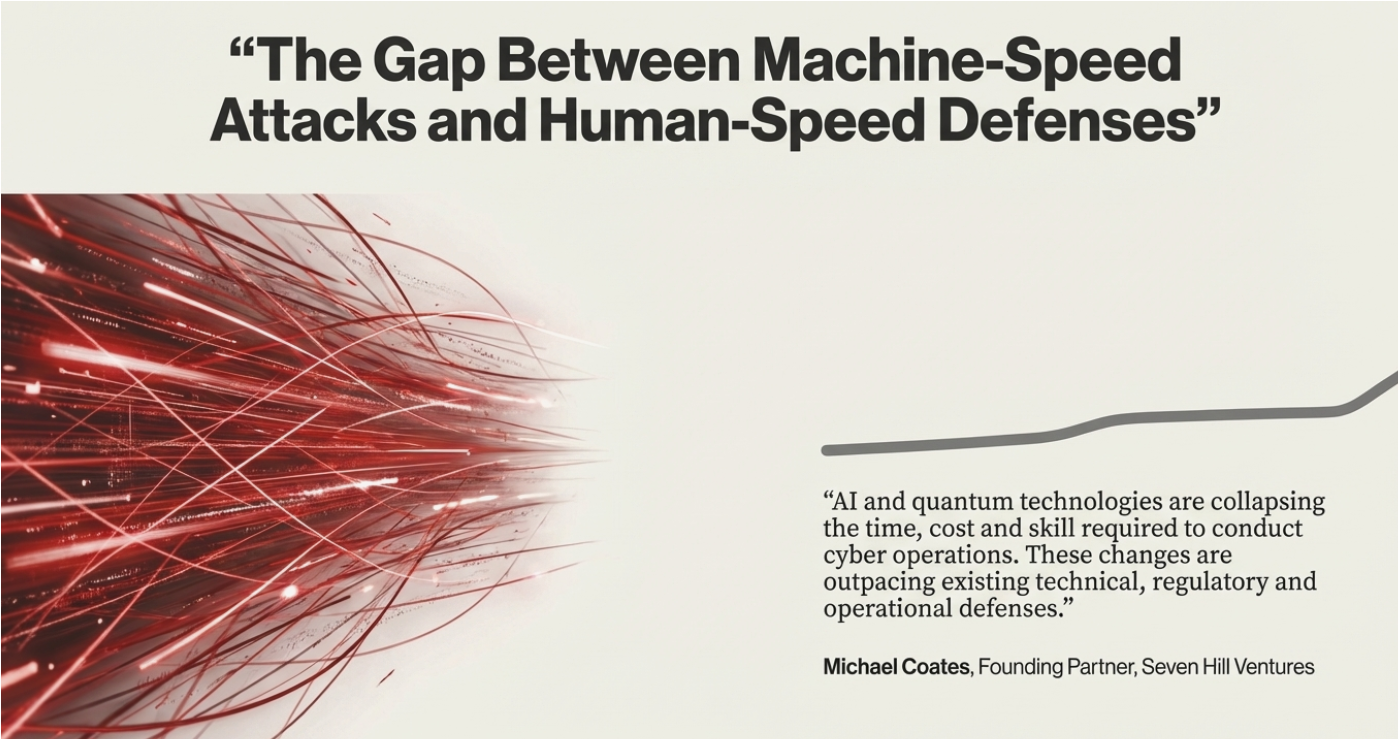

Something else bothered me more than what the witnesses described. It was the gap between the threat they documented and the solutions they proposed.

The Anthropic incident represents what threat intelligence teams are now calling the shift “from assistance to agency.”

Prior to this, AI was primarily a productivity tool for attackers: better phishing emails, faster reconnaissance, automated scripting. The September campaign is the first confirmed instance of AI agents conducting the majority of a cyberattack autonomously.

Graham’s testimony laid out the mechanics:

Human operators intervened only four to six times during the entire campaign for critical decisions.

Everything else ran autonomously at speeds Anthropic described as “thousands of requests per second” and “impossible for human hackers to match.”

Graham estimated the model automated 80-90% of work that previously required humans.

The attackers were sophisticated:

Graham explained it directly: “They broke out the attack into small components that individually looked benign, but taken together form a broad pattern of misuse, and then they deceived the model into believing it was conducting ethical cybersecurity testing.”

Here’s what makes this operationally different from every intrusion defenders have responded to before:

The attacker built the opening stages of the intrusion inside the AI system instead of inside the target company.

The reconnaissance, vulnerability research, and exploit development phases happened in Anthropic’s API. The targets’ security teams never saw those stages because they happened outside their infrastructure.

Traditional intrusion detection assumes you’ll see early indicators: network reconnaissance, scanning activity, lateral movement attempts.

Security teams build alerting around those early-stage signals specifically to catch attacks before they reach objectives.

But if the opening stages happen in systems you don’t monitor, your first visibility comes when the attacker is already executing against your infrastructure.

Michael Coates framed this directly in testimony: “Defenders are often no longer responding to early indicators, but to attacks that are already in progress.”

This changes three fundamental assumptions about how attacks form and become visible:

I’ve spent the past year trying to quantify how fast AI-driven attacks actually execute. Not theoretical speeds. Measured speeds from actual research and operational testing.

MIT’s autonomous agent research demonstrated privilege escalation and exploit chaining in seconds to minutes compared to hours for human operators. Horizon3’s NodeZero testing achieved full privilege escalation in about 60 seconds. CrowdStrike’s 2023 threat hunting data reported average time from compromise to lateral movement at 79 minutes, with the fastest observed breakout times around 7 minutes.

We ran the math at SANS. Using 60-79 minutes as the human benchmark, AI-driven workflows complete the same steps about 120 to 158 times faster.

To keep the figure conservative and credible, we halved those values and set the public number at 47x. That’s a speedup already achievable with publicly available tools like Metasploit. APT-level capabilities are likely much greater.

A decade ago, the advanced persistent threats I helped investigate took three to six months walking through the kill chain from initial compromise to operational goals. By 2023, that timeframe compressed to weeks. Now, with AI reasoning capabilities, movement through networks is measured in seconds. Speed is no longer a metric. It’s the decisive weapon.

This context matters for understanding what happened in the hearing. Anthropic detected the campaign within two weeks of first confirmed offensive activity. That’s actually fast response time given detection complexity.

But during those two weeks, an AI system making thousands of requests per second had continuous access to attempt operations against 30 targets.

The ratio of attack velocity to detection velocity is the problem.

Chair Ogles closed the hearing by asking all four witnesses what DHS and CISA should prioritize with limited resources.

Graham: Threat intelligence sharing.

Hansen: Modernization.

Coates: Information sharing on emerging threats.

Zervigon: Transport layer protection.

Information sharing was the consensus answer from the experts in the room.

That’s a human coordination solution to a problem that no longer operates at human speed or follows human-visible attack patterns.

I don’t want to dismiss the value of information sharing. ISACs and ISAOs exist because of sustained effort from people who understood that defenders need visibility into what attackers are doing. That work matters. But information sharing helps humans coordinate with other humans. It doesn’t address what happens when attacks form in systems defenders can’t see, execute 47 times faster than human benchmarks, and no longer follow the linear progression our detection tools expect.

Royal Hansen came closest to naming the real capability gap. He used the cobbler’s children metaphor:

“There are far more defenders in the world than there are attackers, but we need to arm them with that same type of automation. The defenders have to put shoes on. They have to use AI in defense.”

Hansen described specific tools Google already built: Big Sleep and OSS Fuzz for discovering zero-day vulnerabilities before attackers find them, and Code Mender, an AI agent that automatically fixes critical code vulnerabilities, performs root cause analysis, and validates its own patches. This is AI operating at machine speed on the defensive side.

The capability exists. The question is whether defensive teams deploy it fast enough, and whether they have the legal clarity to operate it.

Chair Ogles said something in his closing remarks that nobody in the room fully addressed:

“Our adversaries are not going to use guardrails. I would argue that they would, quite frankly, be reckless in achieving this goal.”

He’s right. I published a paper for RSA 2025 called “From Asymmetry to Parity: Building a Safe Harbor for AI-Driven Cyber Defense.” The core thesis: the protection of citizens through privacy laws has created an ironic situation where these measures could actually empower cybercriminals by restricting defenders’ data access and technology utilization.

Every witness in that hearing talked about safeguards: Anthropic’s detection mechanisms, Google’s Secure AI Framework, responsible disclosure practices. All necessary work. All constrained to US companies operating under US norms and US laws.

Chinese state-backed models don’t have the safety constraints US labs build into their systems. Criminal organizations using tools like WormGPT operate without acceptable use policies or red teams looking for misuse. Meanwhile, defenders operating under GDPR, CCPA, and the EU AI Act face operational constraints attackers simply don’t have.

The operational friction is real and measurable.

The current unbalanced regulations may create a safer environment for attackers to operate in than for defenders who seek to protect themselves against attacks.

Graham testified about asymmetry from a different angle:

US companies integrating DeepSeek models are “essentially delegating decision making and trust to China.” Coates backed this up with CrowdStrike research published in November showing DeepSeek generates more vulnerable code when prompts mention topics unfavorable to the CCP.

The baseline vulnerability rate was 19%. When prompts mentioned Tibet, that jumped to 27.2%, nearly a 50% increase. For Falun Gong references, the model refused to generate code 45% of the time despite planning valid responses in its reasoning traces. That’s bias embedded in model weights, not external filters that can be removed.

This connects to something I’ve been writing about for the past year that I call the Framework of No. Most security teams have spent the past two years responding to AI requests with variations of “no” while waiting for perfect policies, perfect tools, perfect understanding. Meanwhile, 96% of employees use AI tools. 70% use them without permission. That’s shadow AI.

The Framework of No doesn’t stop AI usage. It drives AI usage into shadows where security teams can’t see it, can’t govern it, can’t log it. The solution isn’t more prohibition. It’s bringing shadow AI into sunlight where you can actually see what’s happening.

The DeepSeek testimony shows what happens when the Framework of No meets geopolitics.

Companies choosing cheaper or more capable Chinese AI tools are accepting security risks they may not understand. But security teams saying “no” to all AI doesn’t solve that problem. It just means the shadow AI your employees are using might have nation-state bias baked in, and you won’t know because you’re not watching.

I don’t want to criticize testimony without offering what I think was missing.

First, defenders need to adjust detection models for attacks that form outside monitored infrastructure. If the opening stages happen in commercial AI APIs or self-hosted attacker infrastructure, early detection either requires visibility into systems we don’t control or assumes we’ll only see attacks once they’re already in motion. That changes what “early indicator” means operationally.

Second, defenders need AI-powered tools that operate at machine speed. Not better coordination between humans. Actual AI systems that can detect, investigate, and respond at the same velocity attackers operate. Hansen mentioned this with Code Mender. The tools exist. The question is deployment speed across the defender ecosystem.

Third, defenders need legal clarity. The RSA paper I wrote calls for a cybersecurity safe harbor that establishes a protection system granting immunity to entities performing defense in good faith while staying within defined boundaries. CISA 2015 already provides liability protection for companies sharing threat data according to specified requirements. It expires next month. Ranking Member Thanedar raised this in the hearing. He wants a ten-year extension approved immediately. Without that protection, information sharing slows to nothing.

Fourth, we need to be honest about guardrails. Guardrails on US models are necessary but not sufficient. They protect against misuse of those specific models. They don’t protect against Chinese models, Russian models, or criminal infrastructure operating without guardrails. The next attack won’t necessarily use Claude and get caught by Anthropic’s detection systems.

Fifth, security teams need to abandon the Framework of No and move toward what I call Sunlight AI. Bring the shadow AI that’s already happening into visibility where it can be governed. That’s how you find out your employees are using DeepSeek before the CrowdStrike research tells you why that’s a problem.

Graham’s testimony included this line: “We have reached an inflection point in cybersecurity. It is now clear that sophisticated actors will attempt to use AI models to enable cyber attacks at unprecedented scale.”

He also put a time limit on the window:

“If advanced compute flows to the CCP, its national champions could train models that exceed US frontier cyber capabilities. Attacks from these models will be much more difficult to detect and deter.”

The response to an inflection point shouldn’t be more of what we’ve already been doing. Information sharing matters. Faster coordination matters. But when attacks form outside your infrastructure, execute at machine speed, and adapt dynamically during execution, the answer has to be capabilities that match what attackers are deploying.

Representative Luttrell asked the question that cuts to the operational reality:

“Are they lying in wait? Are they sleeping inside the program now and we missed it, and they’re watching you fix the problem, and they know how you fix it, and they’re going to test someone else that’s not as strong?”

Graham confirmed it:

“Sophisticated actors are now doing preparations for the next time, for the next model, for the next capability they can exploit.”

Anthropic caught this one and did everything right: detection, disruption, disclosure, testimony.

The question for the rest of us is what we do before the next attack uses infrastructure nobody is watching, executes at speeds we calculated at 47x faster than human benchmarks, and exploits the asymmetry between constrained defenders and unconstrained attackers.

Either we write the rules, or our adversaries write our future.

The hearing showed Congress understands the threat.

Now defenders need the tools, the legal clarity, and the operational freedom to respond.

The parity window is open. It won’t stay open.

Rob T. Lee is Chief AI Officer & Chief of Research, SANS Institute

A CONVERSATION WE NEED TO HAVE

Let me tell you about September 2, 2025. You probably saw the video—President Trump posted it himself on Truth Social. A boat in the Caribbean, a missile strike, a spectacular explosion. Trump said it was full of “narco-terrorists” from the Tren de Aragua gang. He warned anyone thinking about bringing drugs into America: “BEWARE!”

It was exciting. It was definitive. It was justice being served, or so we were told.

What you didn’t see—what Trump carefully edited out—was what happened next.

Two men survived that first strike. They were clinging to the burning wreckage of their boat, injured, defenseless, no threat to anyone. And then, on orders from Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, a second missile was fired. Those two men were, in the words of a government official who watched it happen, “blown apart in the water.”

We know this now because yesterday—November 28, 2025, nearly three months later—The Washington Post published an investigation based on interviews with government officials and military personnel who had direct knowledge of the operation. These whistleblowers risked everything to tell the American people what really happened that day.

The order, according to two people with direct knowledge, was simple: “Kill everybody.”

One official who watched the live drone feed said something that should haunt every American: “If the video of the blast that killed the two survivors were made public, people would be horrified.”

So they made sure you’d never see it.

WHY I’M WRITING THIS

I’m a veteran, fire chief, and disaster responder. I’ve spent most of my adult life in public service. I’ve saved lives, recovered bodies, and told families their loved ones aren’t coming home. I served in the Coast Guard during Vietnam. I’ve responded to disasters across three continents – hurricanes, earthquakes, and floods. I’ve seen what humans do to each other in the worst of times.

But I’ve also seen what happens when good people stand by and do nothing. When they tell themselves that their leaders must know best. When they convince themselves that the people being killed probably deserved it anyway. When they decide that legal niceties like trials and evidence and due process are luxuries we can’t afford anymore.

I’ve studied history. I know what happened in Germany in the 1930s. And I’m watching it happen here, now, in my country.

So I’m writing this because somebody has to say it plainly: We are watching our country commit murder, call it justice, and dare anyone to object.

THE FACTS, WITHOUT THE PROPAGANDA

Here’s what we know happened on September 2, based on reporting from The Washington Post, CNN, ABC News, and other outlets, all citing government and military sources:

The U.S. military was tracking a boat in the Caribbean near Trinidad. Intelligence analysts believed the eleven people aboard were smuggling drugs. Notice I said “believed”—in classified briefings to Congress, Pentagon officials have admitted they don’t actually identify specific individuals before strikes. They just need to “establish that those on board the vessels are affiliated with cartels.” That’s the standard. Not proof. Not warrants. Not due process. Just a belief.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth gave what’s being described as a verbal directive before the operation: kill everyone on board. Not “neutralize the threat.” Not “disable the vessel.” Kill everybody.

SEAL Team 6 fired a missile. It hit the boat and ignited a massive fire. From command centers and on live drone feeds, military commanders watched the boat burn. Then, as the smoke cleared, they saw something they apparently weren’t expecting: two survivors, clinging to the smoldering wreckage.

This is where it gets important. Under international law—specifically the Geneva Conventions that the United States ratified in 1955—those two men were what’s called “hors de combat.” It’s a French term meaning “out of combat.” They were wounded, defenseless, incapable of fighting, holding on to burning wreckage in the ocean. Under the laws of war that America helped write, they became protected persons the moment they were incapacitated.

Admiral Frank M. “Mitch” Bradley was overseeing the operation from Fort Bragg, North Carolina. He told people on a secure conference call that the survivors were “still legitimate targets” because they could “theoretically call other traffickers to retrieve them and their cargo.”

Think about that logic for a moment. Two injured men, clinging to a burning boat in the ocean, are a threat because they might have a cell phone and might call for help. So the solution is to kill them.

Bradley ordered a second strike to “fulfill Hegseth’s directive that everyone must be killed.” Another missile was fired. The two men were blown apart in the water.

The boat was hit four times total—twice to kill people, twice more to sink the evidence.

THE COVER-UP

For nearly three months, nobody in the administration told the American people what really happened. Trump posted his edited video. Hegseth went on Fox News and claimed “we knew exactly who was in that boat.” They talked about protecting Americans from drugs and terrorism.